Politics

The New Eurasian Century

The current crises in eastern Europe reflect more than just Kremlin mischief-making—they reflect the first fruits of an emerging world order that spans the vastness from Beijing to Berlin. Unlike the longstanding liberal status quo, with its roots in classical civilization and the Enlightenment, this emerging alternative draws upon a mélange of German geopolitics, the legacy of Chinese emperors, the Mongols, and Orthodox Russian autocracy. For now, the new Eurasian ascendency encompasses Russia and its expanding list of recovered satellites, as well as China, the world’s premier dictatorship and workshop. But it also now threatens to include Germany, a development that would bring a militarily strong and resource-rich state into alliance with the world’s second and fourth largest economies.

Although the Germans have not yet conceded their ties to liberal democracy, the new Eurasian alliance possesses a magnetic appeal, and shares a common distaste for Anglo-Saxon liberalism. After all, Russia supplies much of Europe’s gas—critical at a time of regulatory-driven energy shortages, and soon to be bolstered by the Nord Stream 2 pipeline—while China has emerged as Germany’s largest export market. The niceties of democracy may be scrupulously observed, but in the end, money talks, along with power, and more than a little anti-American revanchism.

The emerging Eurasian century has ushered in a springtime for dictators who look not to John Locke or James Madison for inspiration, but to autocratic Eastern and Islamic antecedents like the Ottomans, Imperial China, and the Tsars. Democracy, according to a report from Freedom House, is at a generational low-ebb even in Europe. Adjacent Eurasian countries, for the most part, have adopted “hybrid regimes” that combine some democratic norms, such as elections, with authoritarian controls.

A quarter-century ago, the late political scientist Samuel Huntington warned that we were entering an era of geopolitical resentment caused by the West’s perceived mistreatment and humiliation of rival powers, and its attempts to restructure “the world community” in accordance with its own interests. China, in particular, has nurtured an appetite to recover the mighty perch that Confucian civilization once occupied. As late as the 17th century, China was not only more populous and richer than Europe, it also enjoyed an industrial infrastructure that was, at the very least, Europe’s equal.

Liberal capitalism overthrew that order, as Europe’s share of global GDP rose from 17.8 to 33 percent between 1500 and 1913, and China’s share dropped from 25 to eight percent. By 1913, Western Europe’s per capita GDP was roughly seven times that of China or India, while the per capita GDP of the United States surpassed that of these large and venerable nations by a factor of nine.

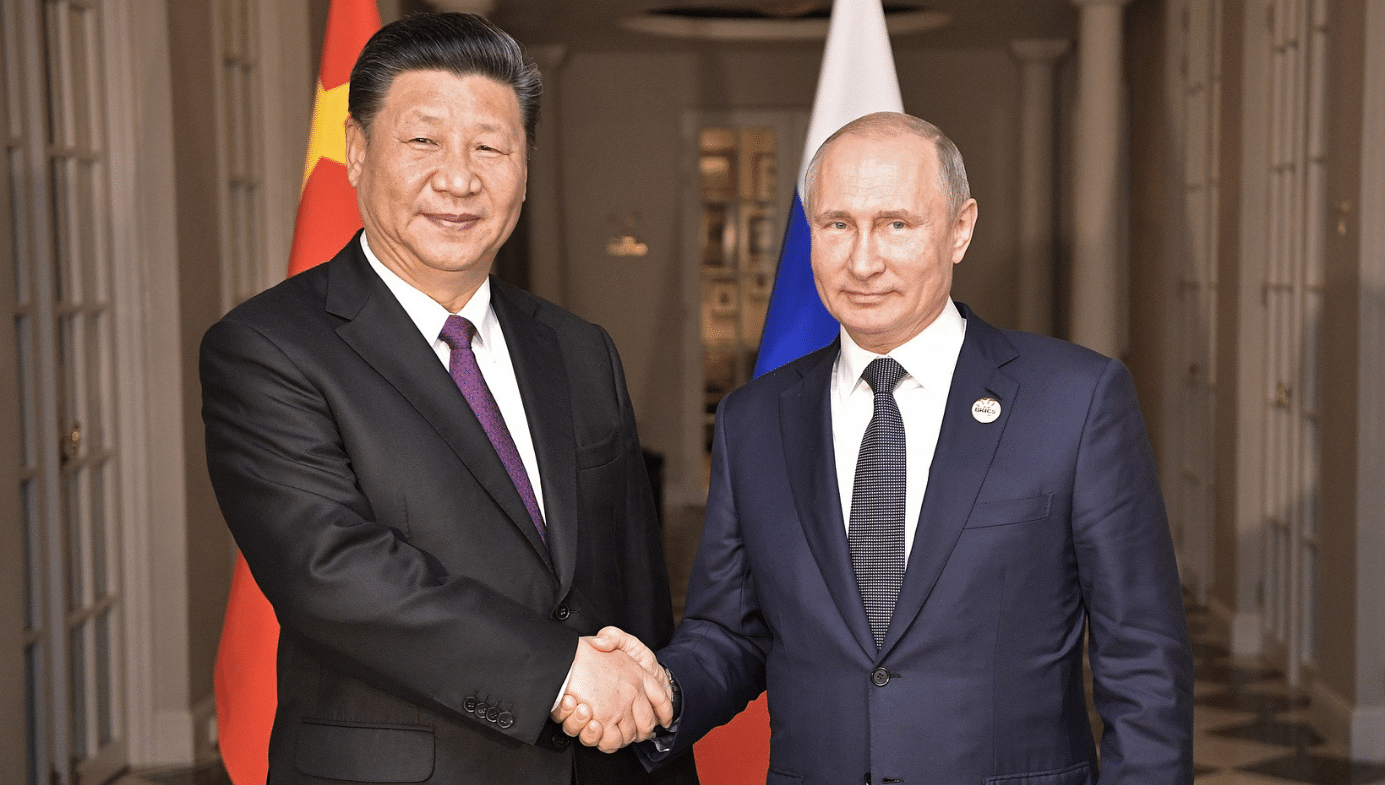

Reversing this state of affairs has been a key objective of China’s leaders ever since. Having opened its economy under the pragmatic doctrines of “socialism with Chinese characteristics” ushered in by Deng Xiaoping, China rose from a negligible part of global GDP in 1980 to 13 percent in 2010. It is projected to reach over 20 percent by 2026. Once awed by the West, Huntington perceived that Asian societies now ascribe their ascendency to “superior culture.” In seeking to reduce their dependence on the old capitalist powers, they would make alliances largely with powers outside the grip of Western liberalism, notably the Islamic states of Pakistan and Iran as well as Russia.

Now the undisputed leader of Eurasia, China achieved its re-emergence without adopting individual political and property rights—the lodestars of Western liberalism once thought to be necessary preconditions to national progress and growth. Today, China is no more likely to become a constitutional democracy than it was under the Mongols or their 14th-century Ming successors. Instead, it has evolved into the model autocracy, based on a system of semi-permanent caste privilege and a technologically enhanced regime of social control. It employs ever-more intrusive means to impose strict censorship, and offers few privacy protections. “If the US has long sought to make the world safe for democracy,” suggests one analyst, “China’s leaders crave a world that is safe for authoritarianism.”

Russia’s Eurasian attachment possesses similarly deep roots. The early 20th-century historian George Vernadsky traced them to centuries of Mongol domination, and then to the Empire’s march towards the Pacific, something that the late Russian historian Nicholas Riasanovksy compared in its importance to the westward settlement of North America. “Scratch a Russian,” the 18th-century French philosopher Joseph de Maistre observed, “and you wound a Tatar.”

This Asiatic affiliation has long been dismissed by the country’s ruling elites, who in Tsarist times, plodded along in French. Then, in the heady days following the Soviet Union’s collapse, Western influence resurged. But in Putin’s Russia, Vernadsky’s theories from the 1920s are once again in vogue. Historian Richard Pipes has observed that, after being marginalized in recent decades, “a kind of cult of Vernadsky has emerged in Russia.” The late Russian historian and Vernadsky biographer Nikolai Bolkhovitinov noted that, once a popular “whipping boy” for his departures from Marxist orthodoxy, Vernadsky is now the object of almost “limitless lauding.”

As in China, revanchism is critical to Russia’s Eurasian lurch. With the West in disarray, Russia seeks to recover, with Beijing’s acquiescence, control of the once-subordinate states on its periphery, from the Central Asian states to Belarus and at least some parts of Ukraine. If China’s goal is to return to the glory of the Emperors, Russia’s is to replicate the territorial successes of the Tsars and Stalin.

History, then, serves not just as prologue but also epilogue. The once-hoped-for integration with the West seems increasingly unlikely. The chance of some long-term “grand bargain” with Moscow now seems, in the words of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, “pure utopia.” Russians today are not likely to oppose Putin’s expansionist gambit. According to the independent Levada Center survey, the vast majority blame the Ukraine crisis on the Ukrainians, the US, or NATO.

In some ways, the mentality of the current Russian state is becoming a non-hereditary modern version of the Tsarist one—militarized, internally controlled, and expansionist. At a time when Pope Francis is moving Catholicism towards a woke species of globalism, the Orthodox Church now serves, as it did under the Tsars, as a support for the state’s nationalist fervor and autocratic rule. Although not nearly as successful as China’s state corporatist model, Russia has also broken from liberal economics by concentrating wealth in the hands of those closest to the Kremlin. These oligarchs are often former officials who benefit from “give-aways” of Russian state assets to select business elites at auctions rigged and controlled by the bidders.

The third piece of the Eurasian puzzle is also the most complex, conflicted, and the most potentially determinative. Germany has had, to say the least, a complex relation with Russia. As early as the 11th century, Germans were interacting with Russia, and under the Romanovs, a number of Russian princes married into German aristocratic families. In the period before the First World War, Russians often looked to Germany for expertise. Catherine the Great, who was German, lured her ethnic compatriots to Russia to tap their enterprise and work ethic. Even after the 1917 Revolution, Germany was the first Western country to recognize the Bolshevik regime. Throughout the 1920s and ’30s, Germany and Russia enjoyed a burgeoning trade which, like today, largely exchanged Russian natural resources for German industrial expertise.

German intellectuals, including some of those close to Hitler, advocated a long-term alliance with Russia and East Asia. The geopolitical theorist Karl Haushofer, who instructed Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess, was among the architects of “lebensraum,” the idea of extending German influence to the east. His wife, however, was half-Jewish, and he did not embrace the crude, and ultimately self-defeating, racism of the Nazis. Instead, he encouraged an alliance of the “three great peoples of the future”—Germans, Russians, and Japanese, then the rising power in Asia. Together, he suggested, they could break the “stranglehold of the Anglo-Saxons.” The German invasion of Russia, which ultimately destroyed the Nazi regime, critically lessened his influence.

Even today, German opinion has a remarkably sanguine view of Russia. In line with popular domestic sentiment, Germany was one of the few Western countries to retain close ties with Russia following the 2014 invasion of Crimea. Astonishingly, most Germans expressed a desire to take a “middle position” between the US and Russia. By 2018, Germans were telling pollsters that they trusted Russia and China more than America, and by 2019, two-thirds of Germans supported closer ties with Russia.

Those ties have warmed even as ample proof has emerged of Russian interference in Germany’s own elections. Russlandversteher (“Russia understanders”) in the German corporate community do not want to see disruption of their profitable trade across Russia and its satellites in “the near abroad.” Kay-Achim Schönbach, head of the German Navy, recently had to resign for suggesting that Russia is a natural ally, a sentiment also embraced by sections of the now-ruling Social Democratic Party.

More importantly, a former SPD Chancellor, Gerhard Schröder, now serves as President of Nord Stream 2’s board of directors. An enabler par excellence, he described his friend Vladimir Putin as a “flawless Democrat” in 2004. But it is the economics associated with the Nord Stream natural gas pipeline that outweigh concerns about human rights, not the politics. Poland’s deputy foreign minister Szymon Szynkowski vel Sęk compared the gas pipeline to the infamous Molotov-Ribbentrop pact which set the stage for Poland’s bifurcation and the murder of millions of its citizens. Nord Stream certainly marks, in the words of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, “a serious geopolitical victory for the Russian Federation and a new redistribution of spheres of influence.”

Like China, Germany craves Russia’s resources. Berlin, and its struggling but still potent industrial economy, also needs the Chinese markets for its high-end goods. German companies are busy building new petrochemical and other high-end factories in the Middle Kingdom, a policy which has led them to “open the door” and “throw away the key.” The result has been that the German administration, usually keen to advertise its concern for human rights, has soft-peddled China’s grotesque record in this area.

Germany’s Eurasian lurch suggests the gradual uncoupling of the country from Anglo-American entanglements. The refusal to provide lethal aid to Ukraine is couched in the rhetoric of German guilt, but Deutschland seems to have few qualms about selling advanced weaponry to less democratic regimes like Hungary, a country savaged by Germany during the Second World War, as well as to Qatar, Egypt, and Algeria. The embrace of dictators like Putin and Xi on the global stage suggests a deeper yearning for a return of order, be it green, corporate, or nationalist, and a turning away from the hated Anglo-Americans, who after all had the nerve to rescue them from National Socialism and then Communism.

The specter of a Eurasian century represents an ominous new chapter in the liberal order. Ironically, it has found “useful idiots” among Western elites apparently determined to continue the rapid de-industrialization and de-moralization of their own societies. As post-nationalist corporate elites call for a “great reset,” high energy prices, and the headlong drive to “net zero,” production will continue to shift to China, powered by ever-more valuable Russian energy and German expertise.

By 2060, when China will likely be looking to reduce its carbon footprint, much of the West may be little more than a vacation spot for rich Chinese and Russian oligarchs. The world will be shaped as it was under the Tsars, Hohenzollerns, or the Ming emperors, each of whom expanded their realms without notable liberal sensibilities. A more well-ordered world could be guaranteed through surveillance technologies that would have tickled the fancy of Hitler, Stalin, or Mao.

The autocratic model, perfected in China and Russia, is already spreading, not only in Central Asia but also in South America, parts of Europe, and especially Africa, where there are now an estimated one million Chinese residents. Many people in these countries take their political inspiration, not from the example of New York or London or even Tokyo, but from the “Beijing consensus.” The growth in sophistication of the Chinese and Russian militaries, while those of the US and the West stagnate, is likely to reinforce this trend.

More important still may be the philosophical challenge. As we are fixed on the Ukrainian conundrum, we are witnessing the greatest assault on liberal values since the end of the Cold War, but we have little remaining self-confidence with which to defend ourselves. The West needs to wake up to the challenge. The Eurasian ascendency raises the prospect of a new and highly autocratic world order. If this trend is to be arrested, we must begin to look at how we are undermining our economic and political future, and helping to create, albeit unintentionally, a new Eurasian century.